Early in my career as a composer, a teacher once gave me an invaluable piece of advice:

"it's essential to learn how a digital tool wants you to think, so that you can free yourself of its bias."

This came up in conversation after I had willingly given up my digital notation tool for pen and paper — and how that choice had transformed my creative output.

I think about this piece of advice often as a designer. How the tools we use put pressure on us to deliver a specific result. And how much the "defaults" of a tool can skew or narrow our process without our awareness.

Design tools for example have come a long way in the last 40 years, from revolutionizing the way we work, to enabling millions to become more creative, to improving the craft year over year. But in all that time they still primarily focus on visual artifacts. And while understandable, this focus can have an effect on a designer's output.

In the early 1970s, a series of landmark papers by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman were published exploring Judgement under Uncertainty. And one thing they discovered was how knowledge or information easily available to a person could bias their thoughts and actions towards those things — known as the availability heuristic.

Studies related to knowledge and decision making have also shown that people with less knowledge and fewer cues are more likely to make poorer decisions. And this raises an important question about digital tools:

In the context of a design tool like Figma, how much does the lack of an option influence a designer into producing a certain result?

Enter accessibility.

Knowledge, and the Unseen Needs of Accessibility

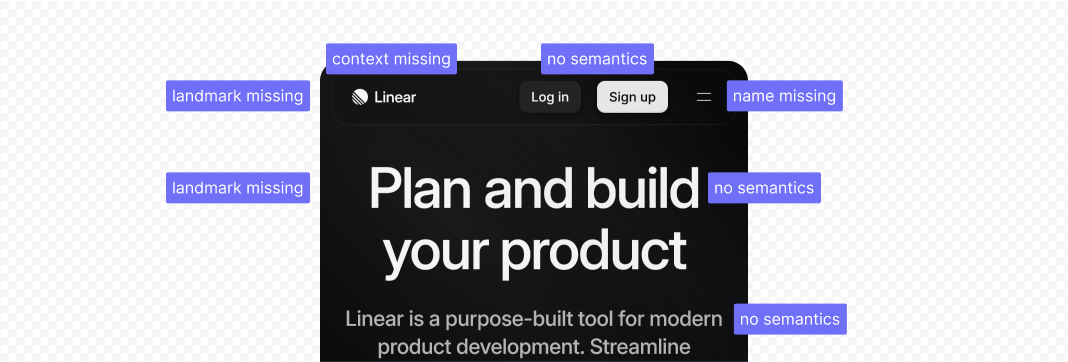

When building an accessible product, there are a significant number of details that are inherently non-visual — things modern design tools aren't built to handle:

- The name or semantics of something in context.

- Meta-information about the page.

- Or, the many ways people can interact with an element.

When a design tool doesn't help a user manage one of these details, designers need to rely on their own knowledge or a support system (like co-design activities) to ensure those details are covered. And this comes with a fair bit of risk if that knowledge is missing. As Richard Larrick and Daniel Feiler note in Expertise in Decision Making:

"…domain ignorance [...] leaves the decision maker blind to important interactions among factors that may be obvious to an individual experienced in that domain."

And this supports the hypothesis that direct support from a design tool could improve a contributor's output. In fact, they even state this more directly, saying:

"Distilling expert knowledge into a decision support system can dramatically improve experts’ consistency."

So, let's talk about how we could do that.

Before continuing, I should clarify that I am specifically talking about tools designed to help build digital products, like Figma, Sketch, Penpot, and others.

Various Ways Design Tools Impede Accessibility

There are many different ways that accessibility can be impaired in a visual design tool. And the following are a few major categories.

The most practical challenge is that often, non-visual information is not supported by a tool (or only partially). This both adds difficulty to making something accessible, and may force guesses if the right information, knowledge, or process isn't in place.

The nature of a visual communication tool also encourages designers to focus in on this aspect, and may blind them to details that fall outside of this medium. And other kinds of influence can further encourage this narrowing, like a lack of time.

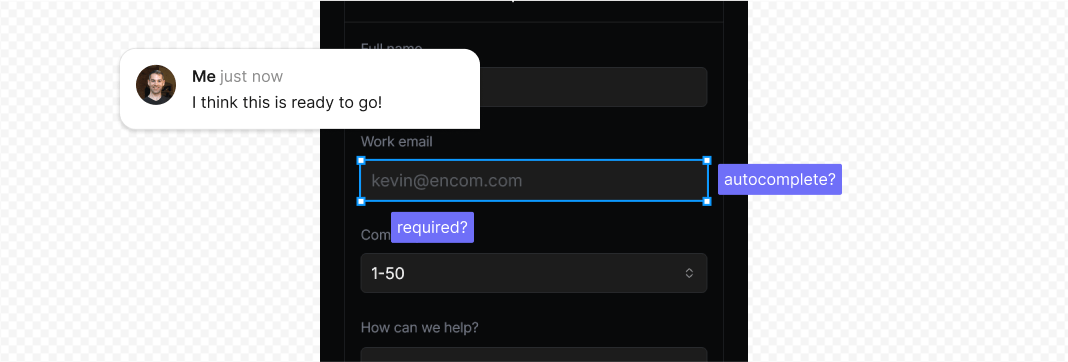

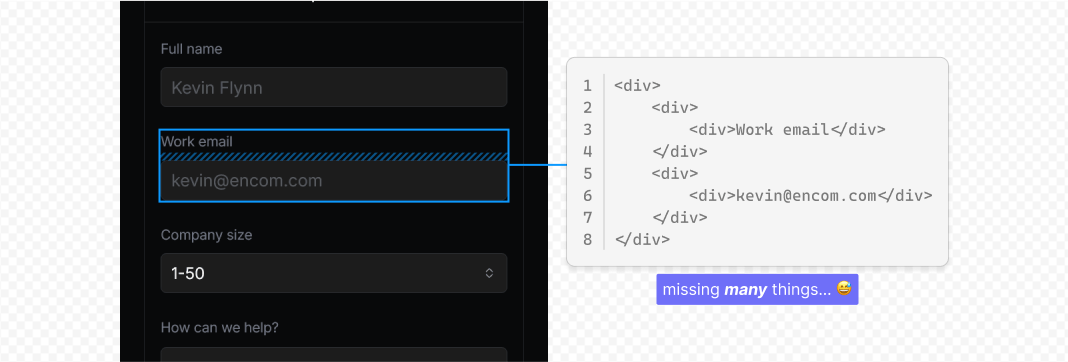

Additionally, many tools have made efforts to bridge the gap between design and engineering. But the code that's produced often lacks context or specificity, and as a result isn't usable until it has been edited by a human; and that's not always possible.

There are plenty of tool-specific examples as well. As much as I love Figma's Community, it has allowed Figma to offload what are ostensibly central challenges of a product's experience to users to solve. And this has the potential to seed that a topic isn't actually that important, or will be invisible to a designer because of how it's positioned. And I'm certain Figma is aware of this as they've done a number of things to close a few gaps — like introducing Dev Mode, or committing to initiatives like their Resource Library or Shortcut.

Ways Our Current Tools Can Improve the Practice

When I began exploring this challenge, there were three questions on my mind with how design tools could help accessibility work:

- What decision support systems do we need to provide the most help?

- Where is the most impactful place in the user journey to provide these systems?

- How do we provide the right breadcrumbs to expose and promote the use of these systems?

But before answering any of them, we need to talk about limitations.

There are certain kinds of accessibility challenges that design tools are incapable of measuring. For example, the level of anxiety that an experience might place on someone with ADHD. And as a result, this leaves more deterministic challenges for us to consider. Things like

- what something is called or how it's described,

- properties or data about something,

- meta relationships,

- interactivity and behaviors, or

- other details that can easily be measured.

And these challenges directly relate to the first question about decision support systems.

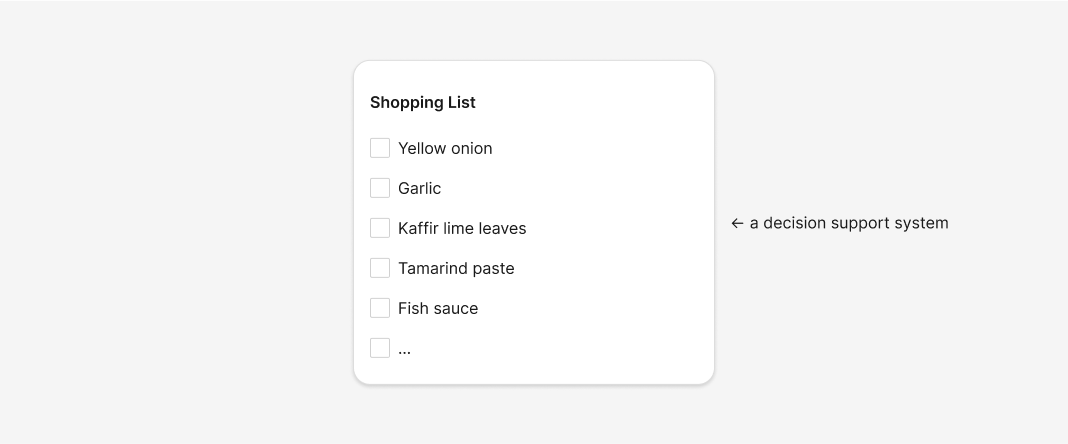

A decision support system is a cognitive aid that can be used help improve the consistency and outcome of a process. And a shopping list is a great example of one.

In the context of a design tool, the underlying goals for these systems are still the same: they should help designers be reminded of, and build consistency with an accessible outcome; like making sure that structural landmarks are identified.

But what might these systems look like? And where do we place them to have the most impact? There are many different possibilities depending on which design tool is being considered. So I'd like to simplify the remainder of this topic by focusing on Figma specifically.

Systems to Improve Accessibility in Figma

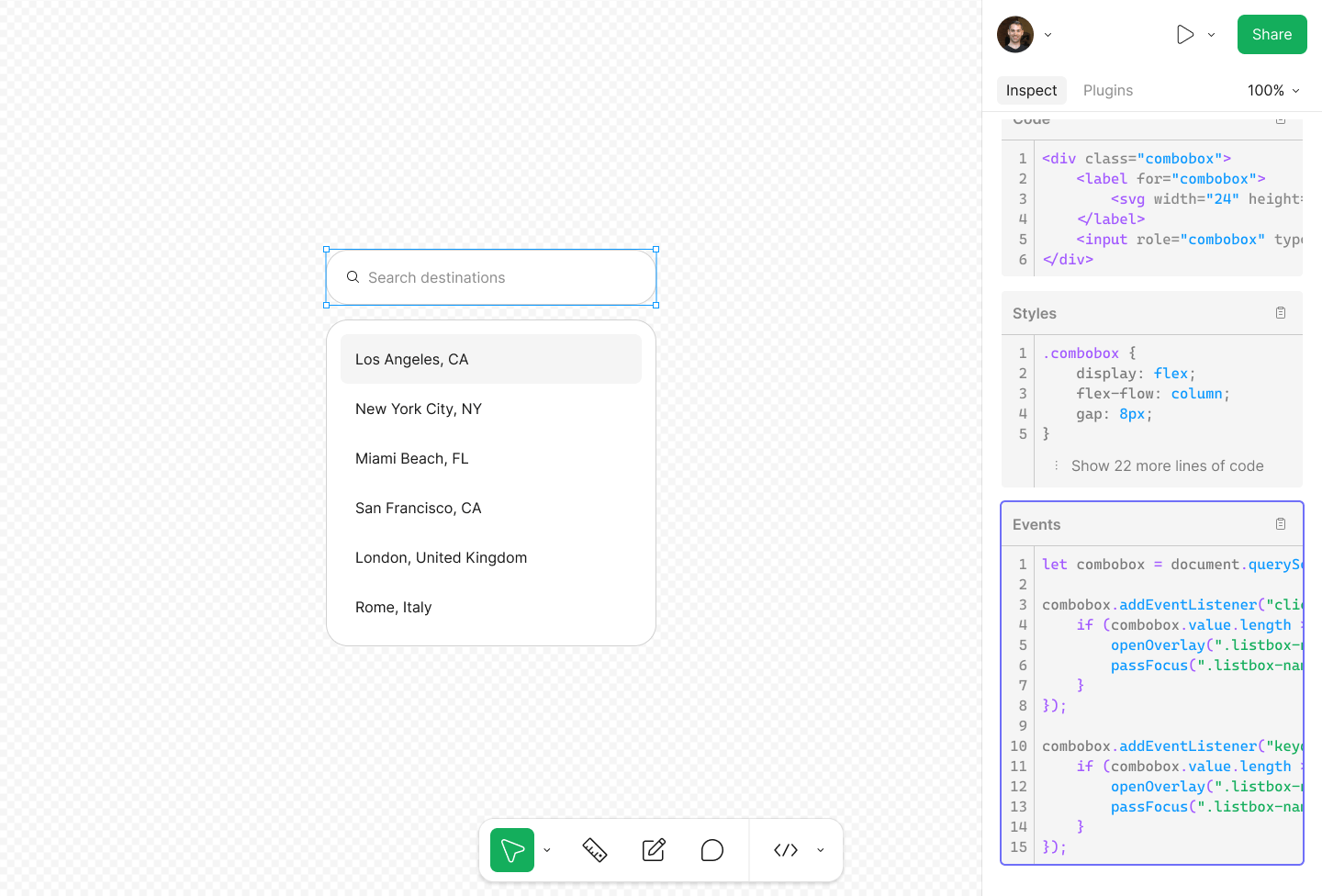

Writing can only do so much, so I built a prototype that you can experience yourself to get a better sense of how these new systems might work.

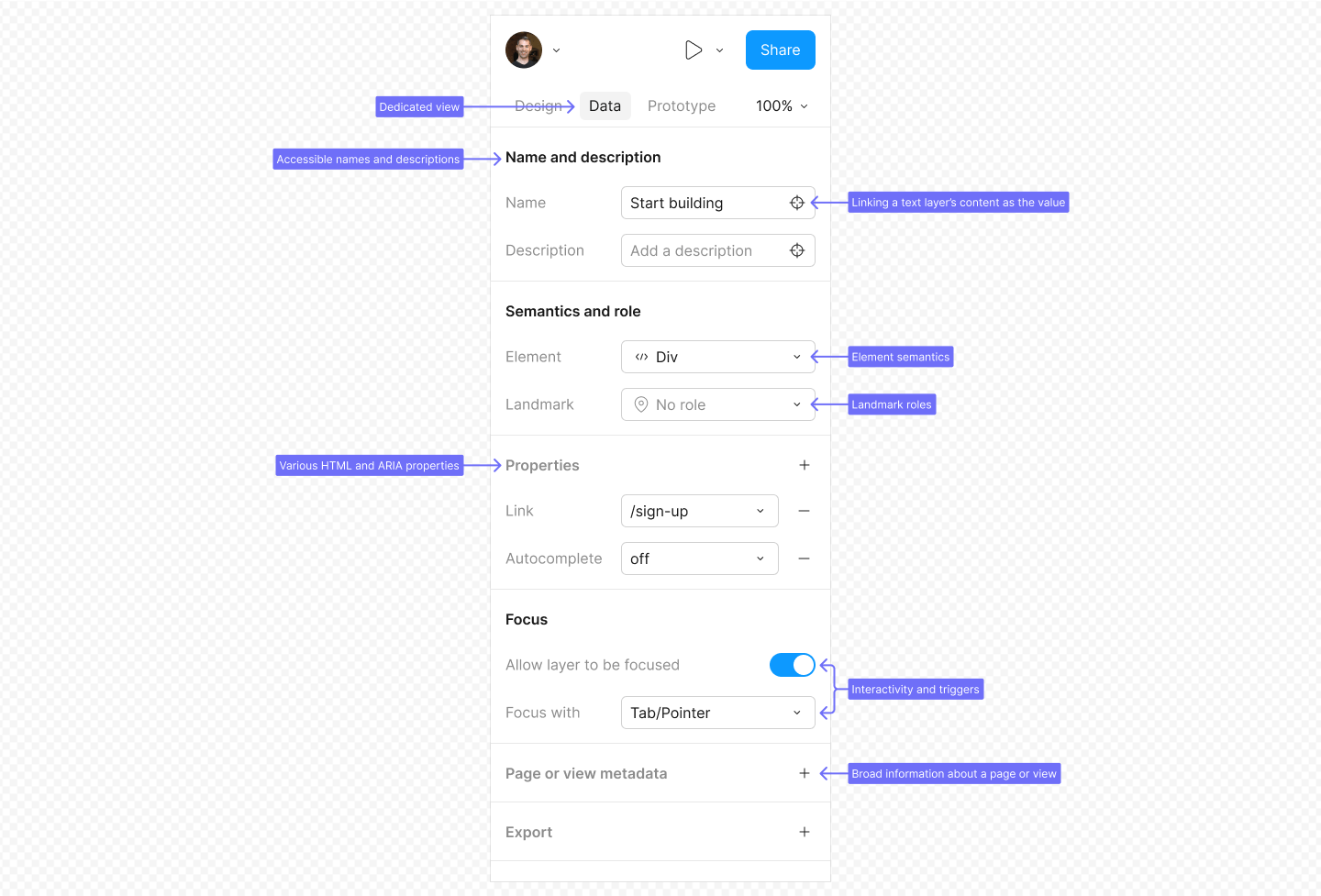

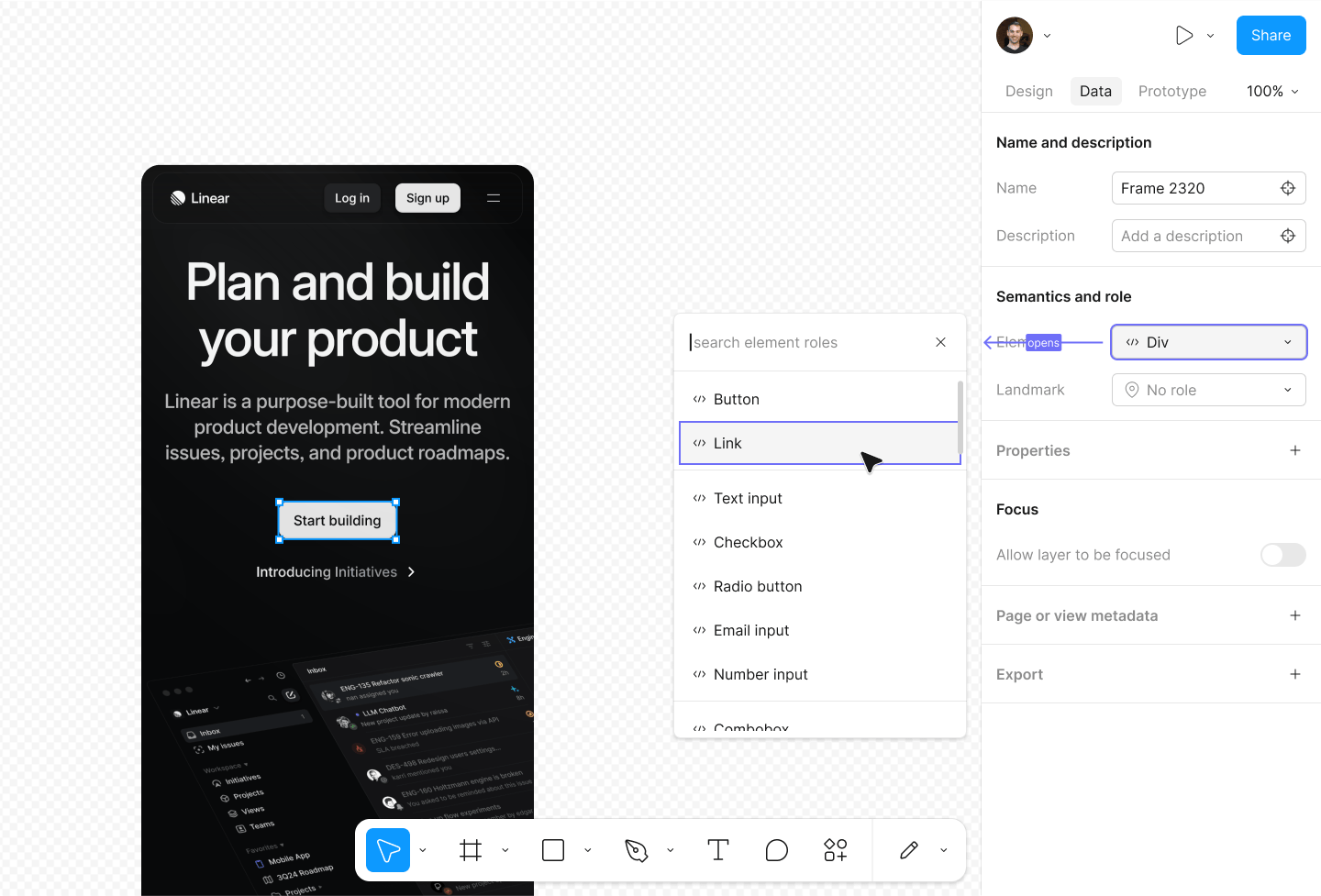

Props, Data, and Non-Visual Information

We've already noted that a great deal of information about a product is non-visual. And Figma partially supports this challenge with Dev Mode and Annotations. However, one major shortcoming with this is that the nature of an Annotation reinforces the idea that "this information is not an intrinsic part of the product."

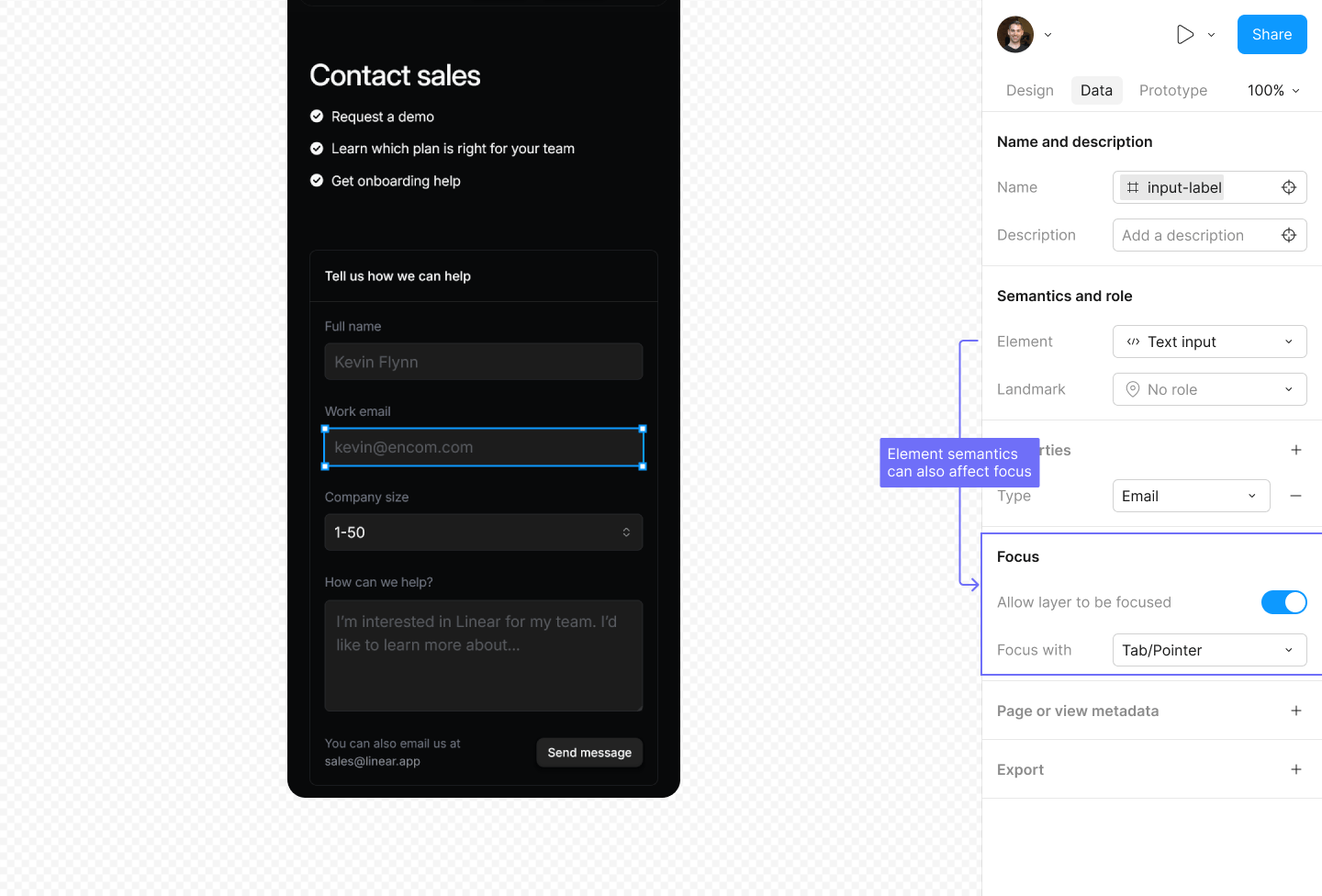

Given this and other weaknesses that exist, a more effective approach would be to build a dedicated tab in the properties panel (in design mode) that helps users include many different kinds of non-visual "data." And this approach provides a lot of benefits:

- Information is highly discoverable as a direct part of the design experience.

- Deterministic properties help users in their learning process.

- A dedicated tab provides better clarity with groups of related information.

- It enables simpler and more robust interactions around managing this information.

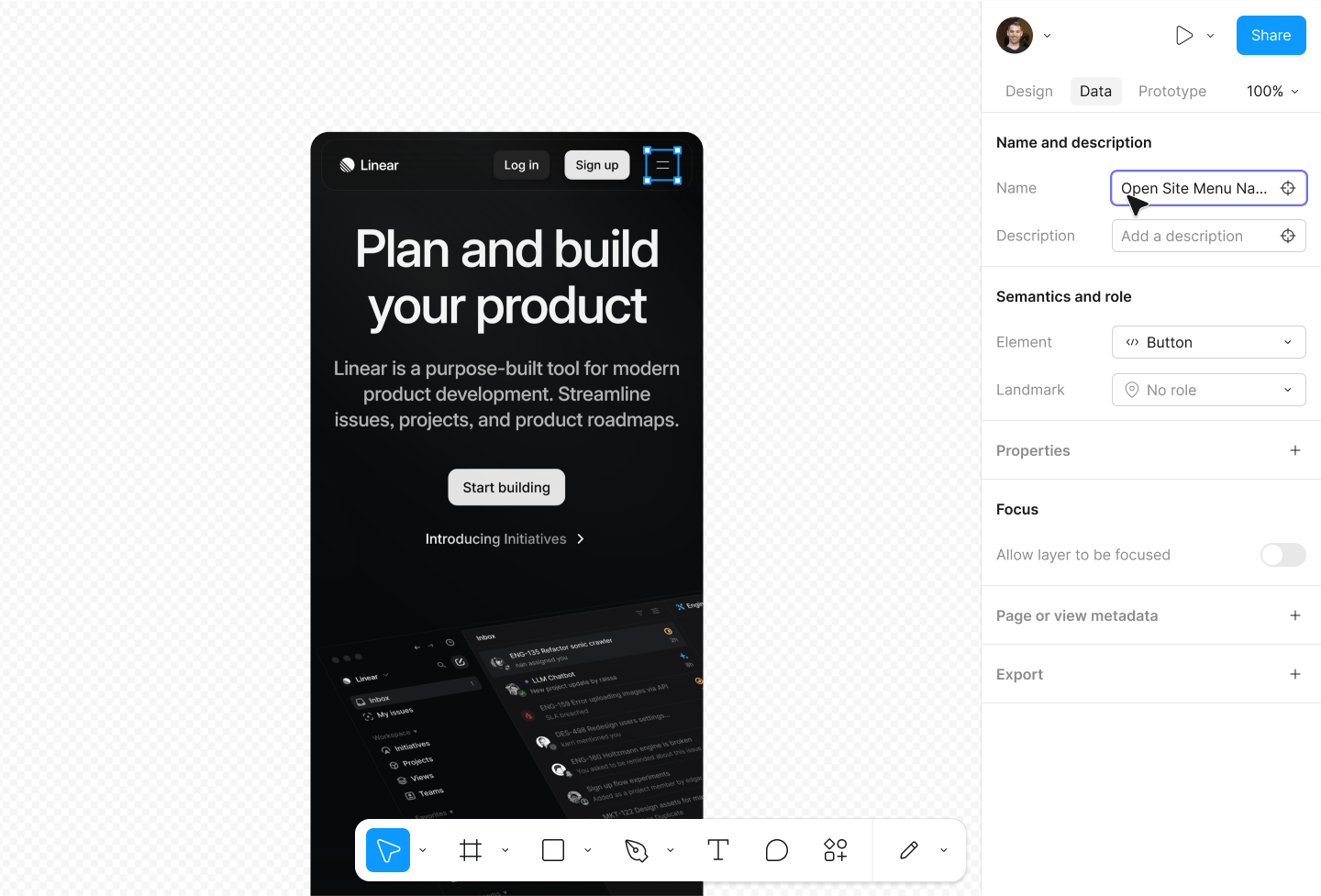

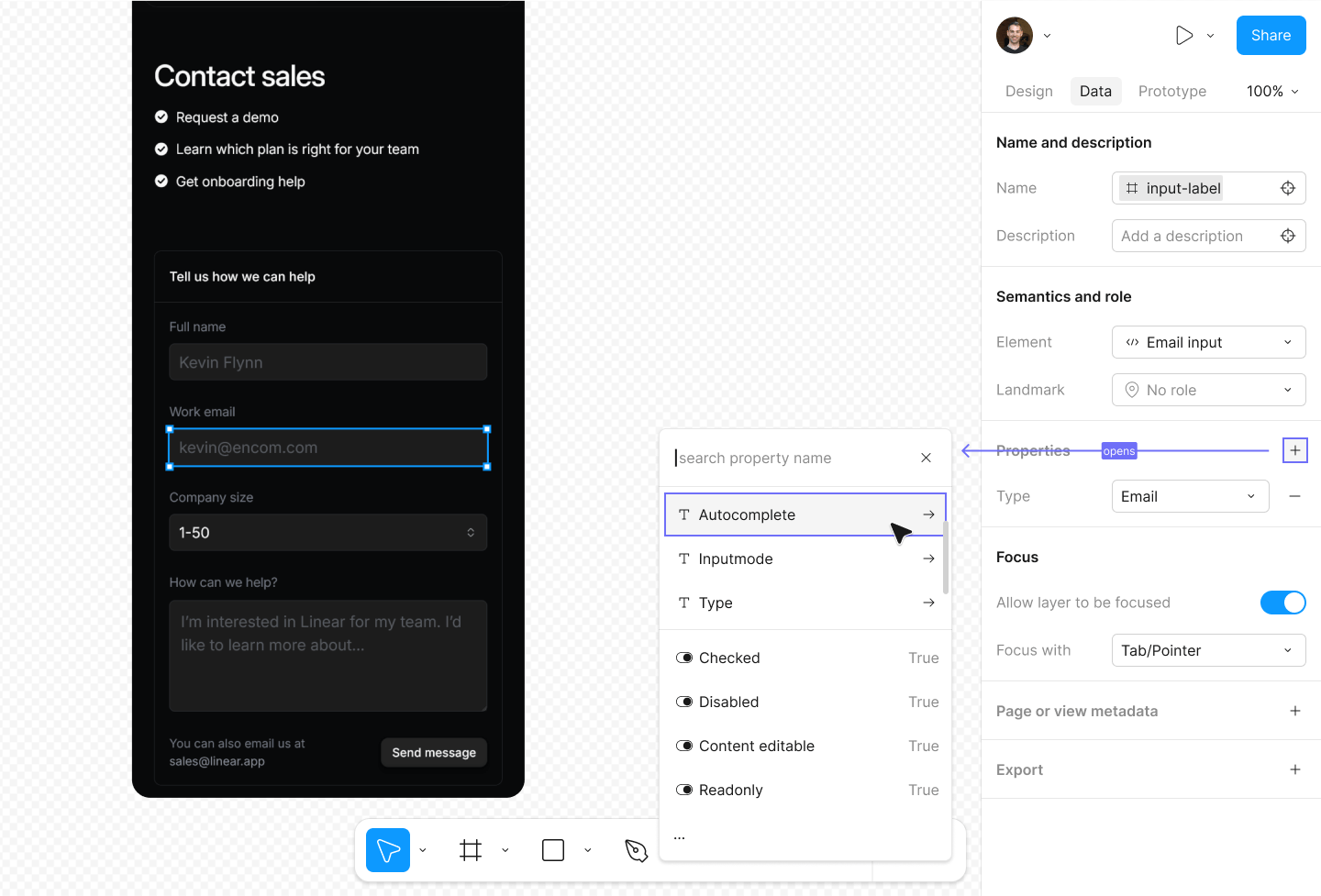

More practically, users can leverage these new tools to capture different kinds of important information such as applying element semantics, giving a layer the proper name, or adding properties to help describe the functionality and behavior of something.

There's an even bigger benefit to this approach too. By directly supporting real properties Figma would be able do a lot more, such as

- articulate this information directly in code;

- provide logic for when properties conflicted or included additional effects; and even

- help automate certain kinds of decision making (assigning the button element to a component named "button").

And testing this new approach with designers showed that — even with the complexity of this additional data — these changes both helped designers be successful and had the potential to greatly improve collaboration with developers.

Challenges with this Approach

As much I like this approach, it does come with a few big challenges however. Shifting the entire focus of Figma so that "design mode" is more holistic

- increases the risk of this process being left undone as information could be pulled away from people with more domain expertise (developers); it

- places more emphasis on the challenge of "how do you better integrate developers into the design space?"; and

- has the potential to place a lot of pressure on designers to "learn how to code."

And testing echoed some of these concerns as well. In particular, how this approach does not entirely solve the literacy problem that exists, as many designers are unfamiliar with what a "combobox" is, or when it's appropriate to apply a "landmark role."

Simulating the Human Experience

Another big area of accessibility work is attending to the different ways people actually experience a product. From their ability to capture stimuli, to processing information, to how they interact with a product. And a lot has been done to address these experiences with tools for color contrast, vision impairments, and other needs. But these tools only partially address this challenge and always add some amount of negative friction to this kind of task.

So how could Figma better support designers here?

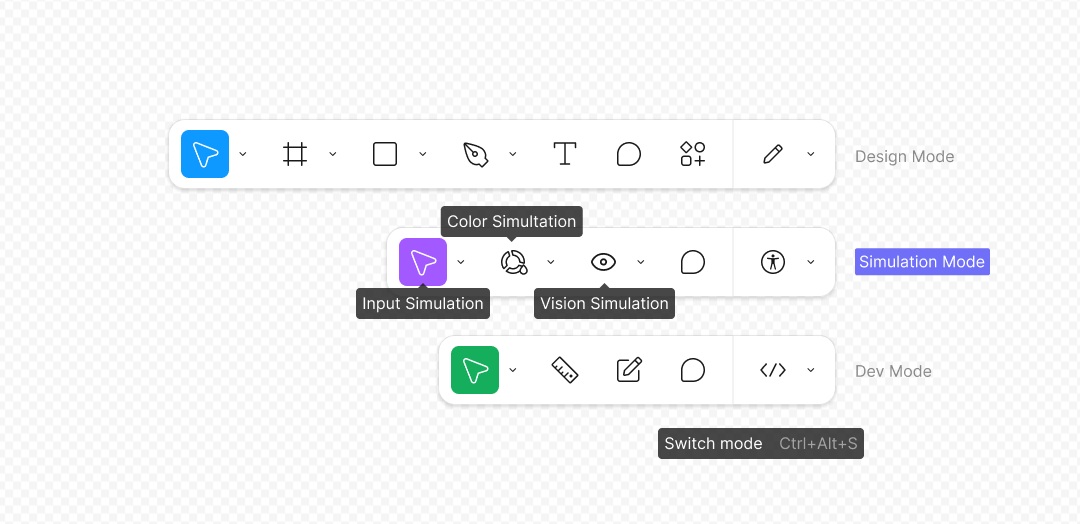

Extending the modality of Figma to be able to support these kinds of variations in the human experience is one way to approach this problem. And a dedicated mode for this has a few important benefits.

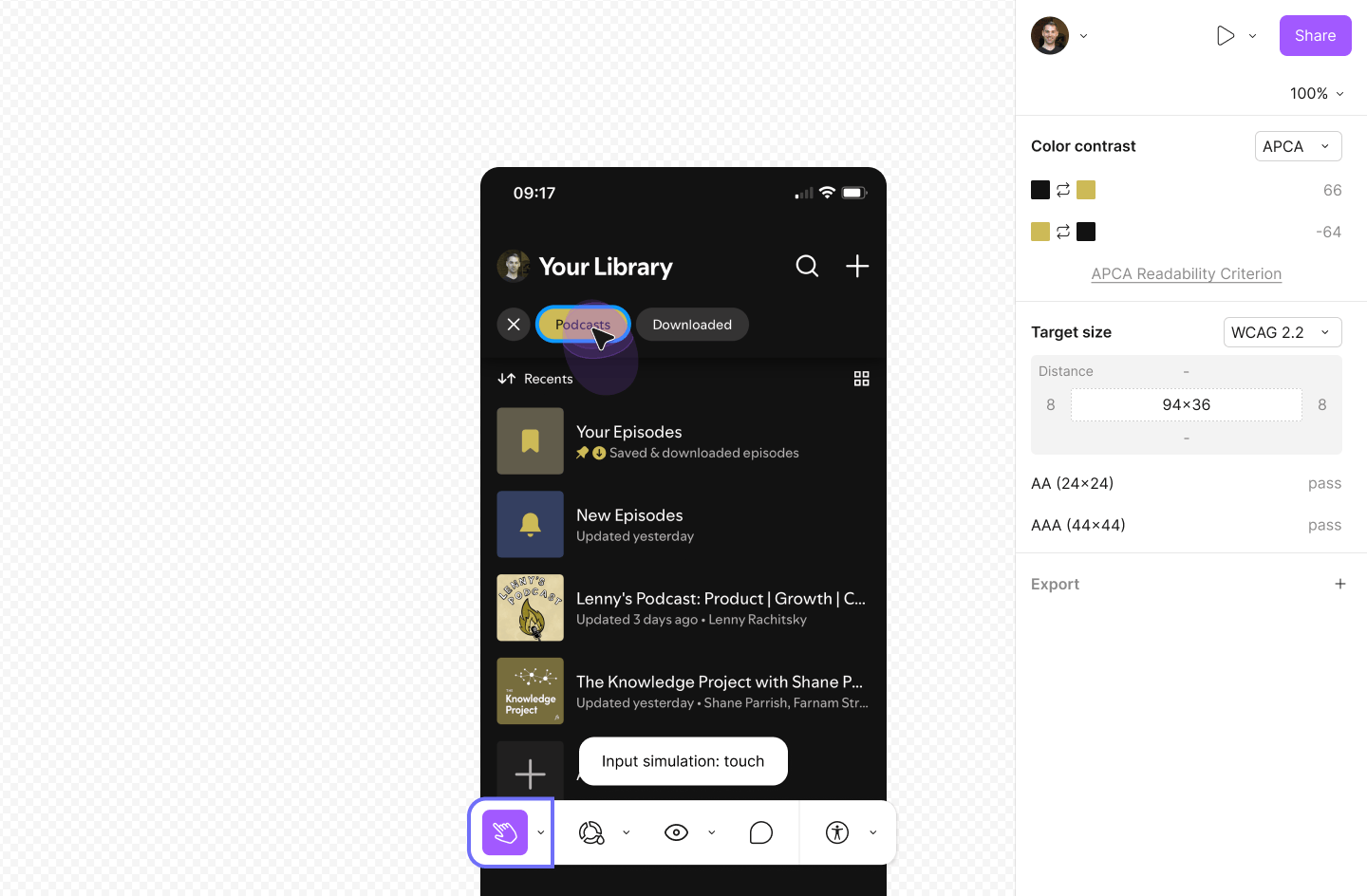

First, it allows designers to explore many different experiences, such as a person who has a vision impairment like cataracts, or uses their fingers to interact with the product.

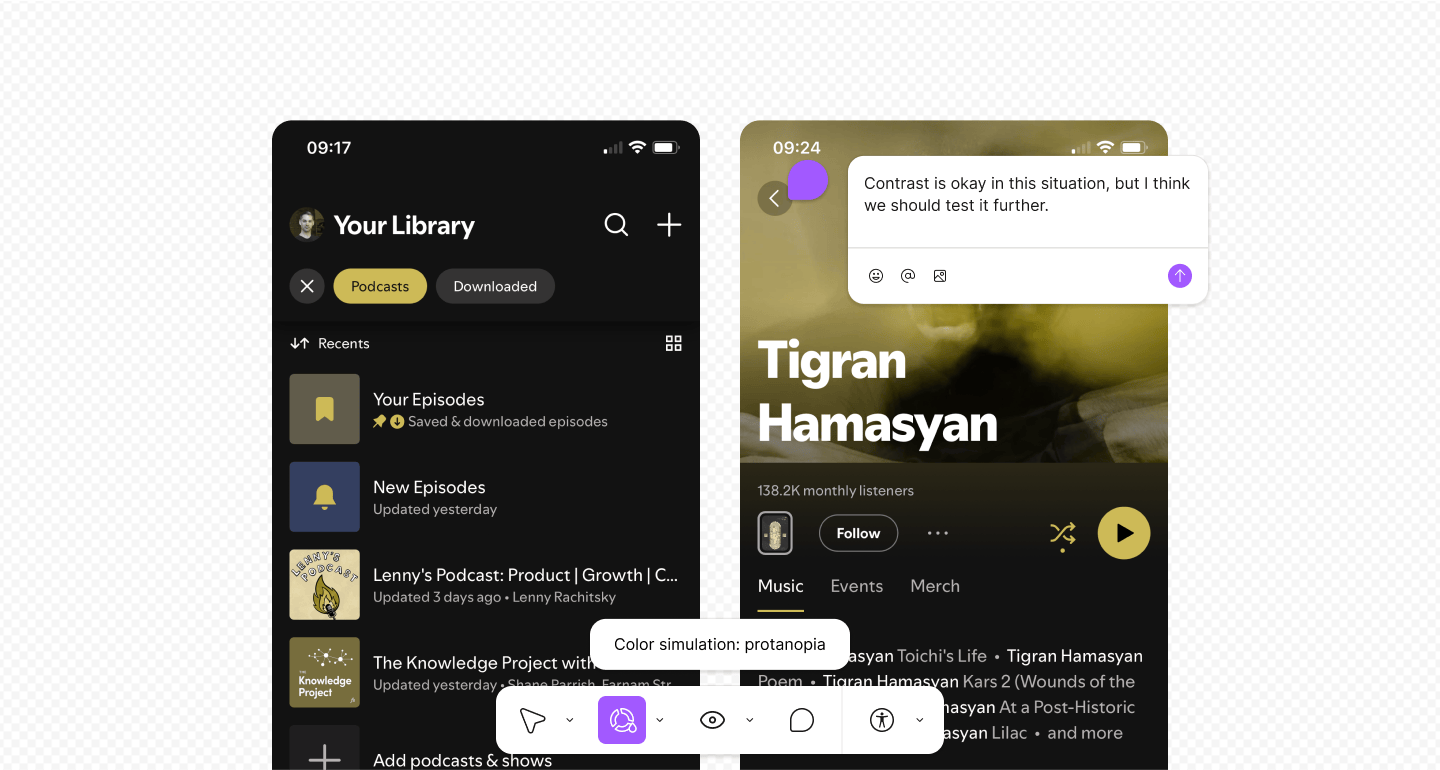

As an example, designers could easily simulate a color deficiency like protanopia to see how a person with red-green colorblindness might experience the product:

The other big benefit is that a dedicated mode enables a more robust experience around measurements. Tools could be configured to use specific rules, and these measurements could also facilitate more learning opportunities with the criteria they are using. It would even be possible to measure specific situations, like contrast under a specific type of colorblindness:

Every designer I worked with was excited about this new "simulation mode" in testing, with sentiments ranging from "really useful" to "simply phenomenal." And this feedback was really encouraging.

Prototyping and Better Interaction Support

There's one last situation I'd like to cover. And it's an interesting one because on the surface the solution doesn't look like an accessibility-focused improvement.

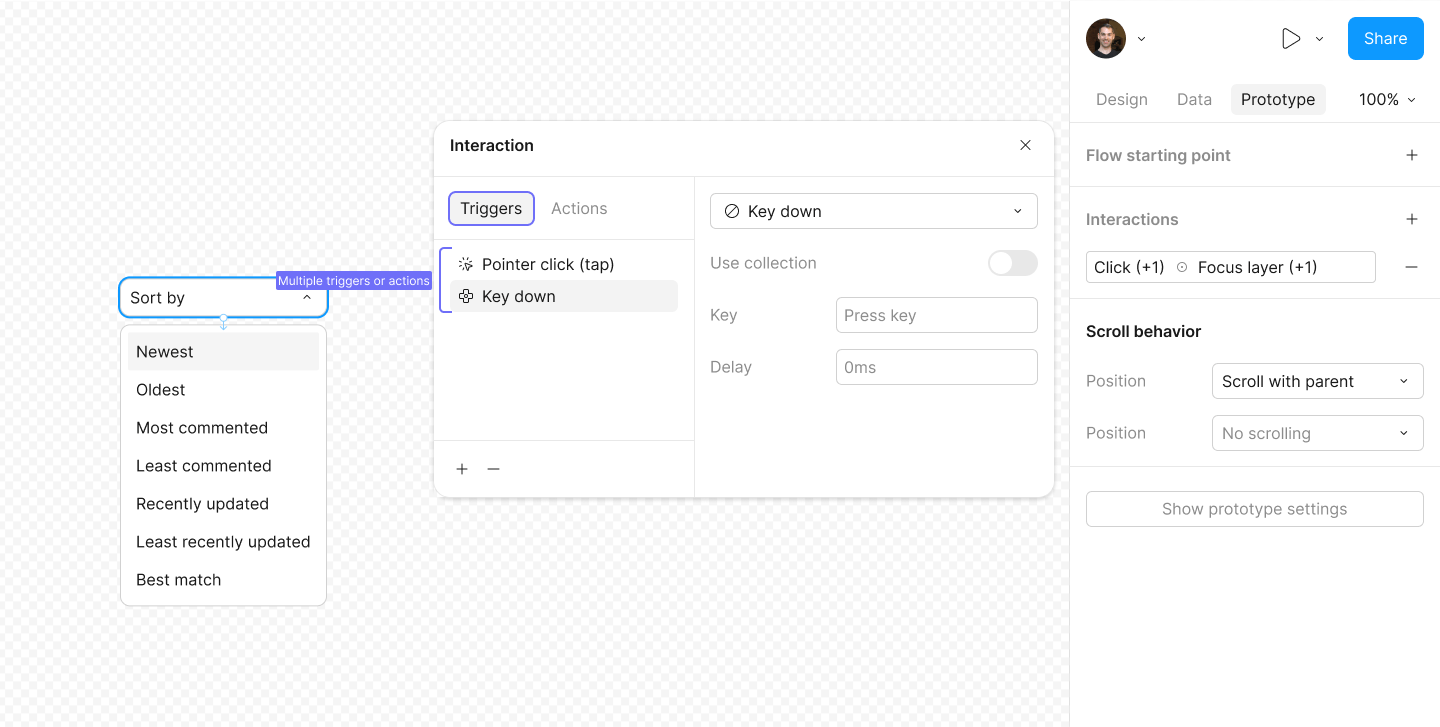

One of the biggest challenges in accessibility is designing a great interactive experience for everyone; especially for those using a keyboard. Thankfully, Figma already has a partial solution to this challenge with prototyping features. And this presents a great opportunity to improve two things at once: creating more accessible outcomes by helping designers build better prototypes. There are some challenges to address however.

The biggest challenge is with how Figma's prototypes currently work. And a few barriers are that

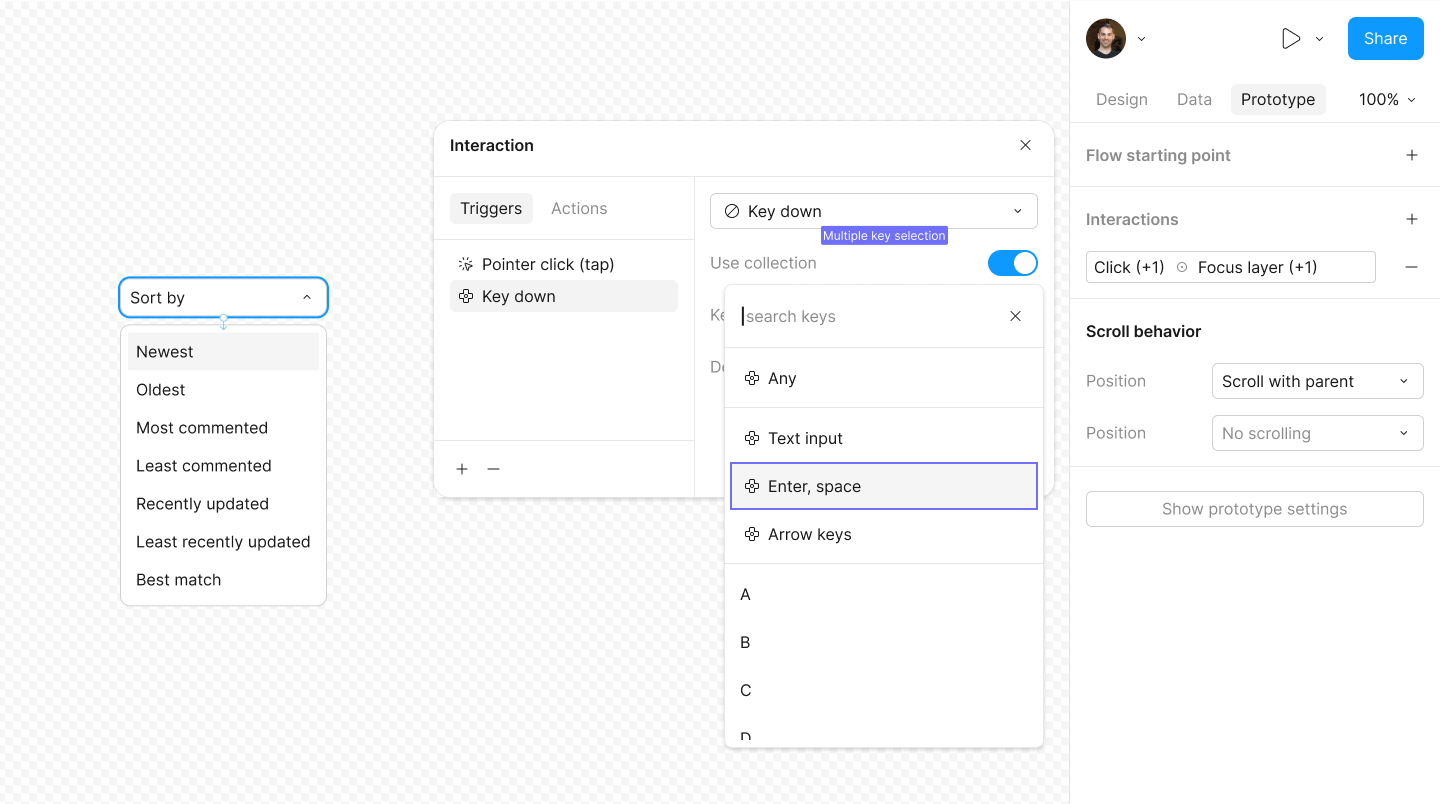

- when keys are selected as a trigger, only a single key can be assigned;

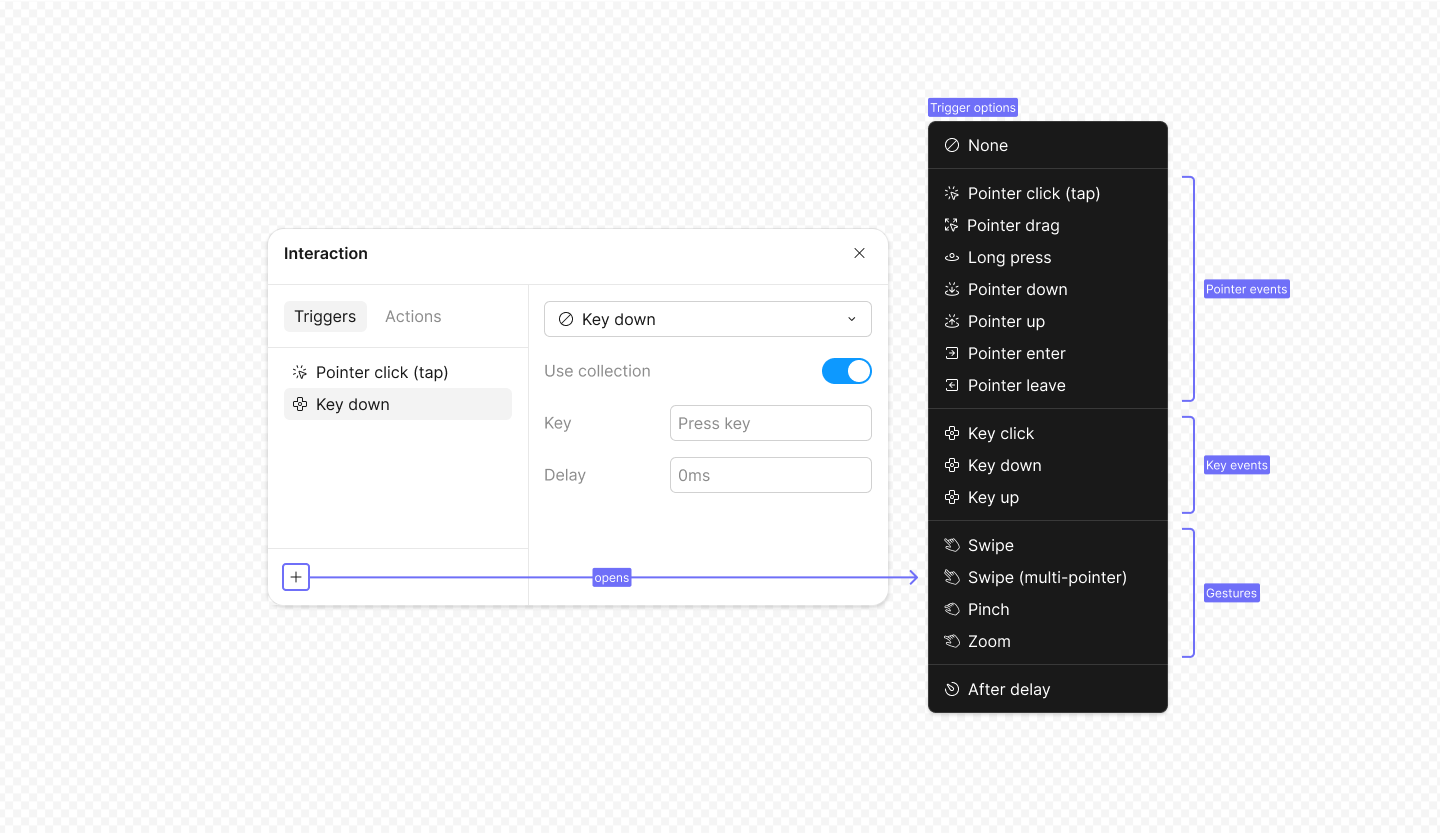

- only a small number of trigger options are available; and

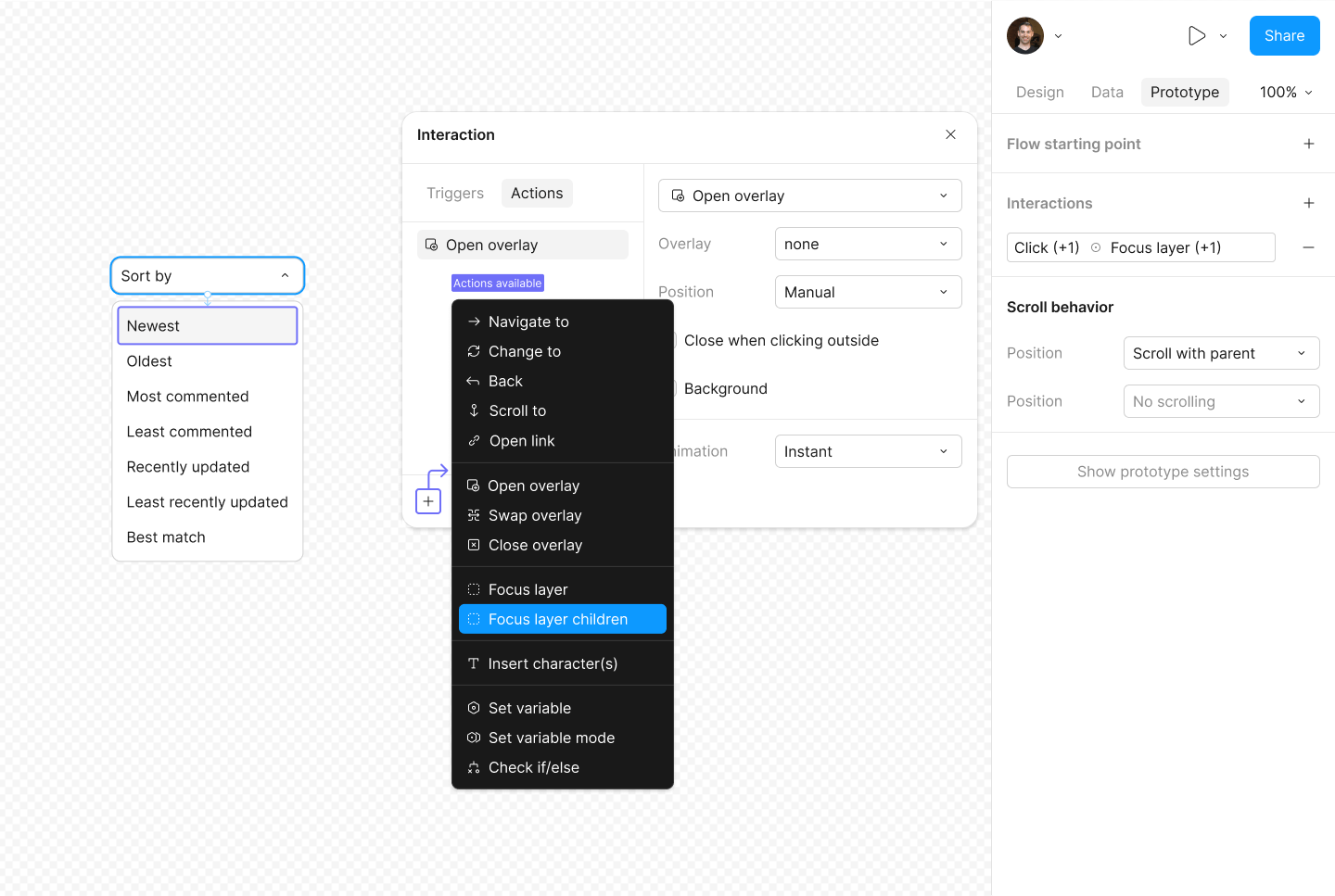

- the concept of focus does not exist.

In addition, restricting actions to a single trigger adds unnecessary friction to building complex behaviors. And addressing this workflow improvement first would improve the overall experience.

The first adjustment lets a designer include multiple keys for an action, as there are many situations where a collection of keys are equally valid triggers.

The biggest change however is in the types of triggers designers can choose. And by changing them to match real events, not only are many more kinds of prototyping behaviors available but accessibility needs (for multi-modal experiences) can also be achieved.

The last change is a small, but impactful one. Prototypes in Figma currently support keyboard use with screen readers. And while helpful, in practice this approach creates some awkwardness as the concept of "focus" doesn't really exist. And that's a crucial piece that's missing.

Thankfully, this can easily be remedied by giving designers the ability to mark specific layers as being "focusable" and letting actions pass focus to those layers. And this would allow prototypes to behave a lot more like a real product.

Earlier when talking about non-visual information, I also included a section for focus that I didn't note. And I did so because not only can it be a real design property that can be affected by other properties, but it also helps set the foundation for essential navigational behaviors as well.

All in all, these changes greatly improve the kinds of prototypes and accessible behaviors that designers can create. But they also help Figma to become a much better source of truth by capturing and communicating this information in a measurable way. And that's a big opportunity for Figma to then translate these behaviors into real, accessible code for developers to build from. And many of the designers I worked with echoed these sentiments.

Real Value Exists with Direct Support

During this project I worked with a number of designers with different levels of accessibility experience to help build more confidence in this hypothesis. And the feedback they gave in testing the prototype I built was very positive overall: from the improved support and capabilities designers would gain, to the collaboration improvements, and generally how interested they were in using these tools in their work. And I need to take a moment to thank them for their time and feedback on this project as it was invaluable.

I strongly believe that a great accessibility experience is only achievable when it's a natural part of the design process. And I hope that this exploration has helped to persuade you that there's real value in building a more holistic and accessible product tool.

And if "…distilling expert knowledge into a decision support system can dramatically improve experts’ consistency" as Larrick and Feiler note, then I'm hopeful about the impact these adjustments could have on accessibility work overall.

Resources

- Judgement under Uncertainty, Tversky, Kahneman

- Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability, Tversky, Kahneman

- Expertise in Decision Making, Larrick, Feiler

- The WebAIM Million, WebAIM

- 94% of the Largest E-Commerce Sites Are Not Accessibility Compliant, Baymard Institute